In the perpetual darkness of the abyssal zone, where sunlight never penetrates and pressures crush all but the most resilient lifeforms, an extraordinary ecosystem thrives against all odds. The Whale Fall Gardens—vibrant oases of deep-sea biodiversity—have captivated marine biologists for decades. These sprawling communities emerge around the skeletal remains of fallen whales, sustaining complex food webs for up to a century after the cetacean’s death. Recent expeditions to the Mariana Trench and Mid-Atlantic Ridge reveal that these calcium-rich graveyards harbor more species than previously imagined, rewriting our understanding of survival in Earth’s most inhospitable realm.

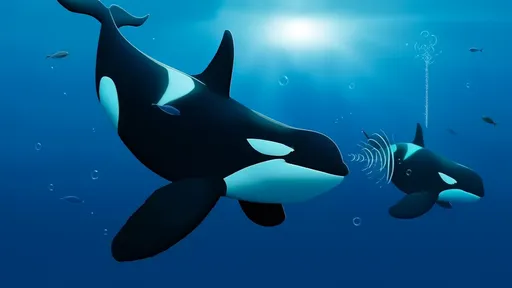

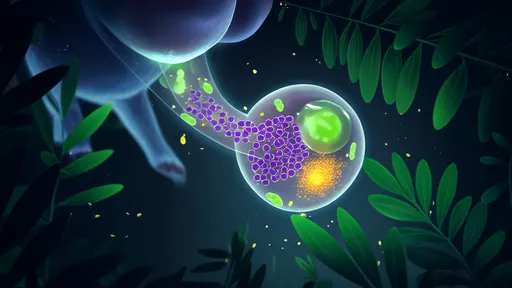

The journey begins when a 40-ton leviathan sinks through the midnight zone, its carcass plummeting like a slow-motion meteorite. Upon impact with the seafloor, the whale’s body becomes a biological supernova, releasing nutrients equivalent to 2,000 years of normal organic detritus. Within weeks, hagfish and sleeper sharks tear through blubber in frenzied scavenger events dubbed "the mobile scavenger phase." But the true marvel unfolds years later, when only bones remain. Chemosynthetic bacteria transform lipids trapped within the skeleton into sulfides, fueling tube worms, clams, and blind crustaceans adapted to this peculiar buffet.

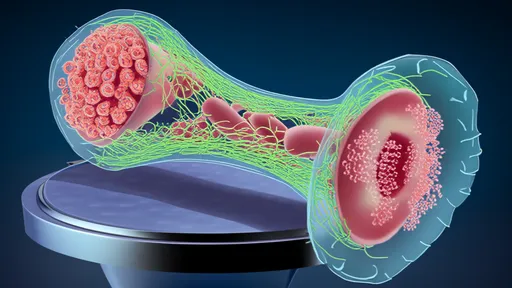

Researchers from the Schmidt Ocean Institute recently documented a 15-meter gray whale skeleton off California’s coast hosting 207 species—45 previously unknown to science. Among them was a translucent snail with hemoglobin-rich blood, evolved to extract oxygen from the bone matrix. "These aren’t just random organisms clustering together," explains Dr. Miriam Goldstein. "We’re seeing specialized bone-mining ecosystems with tiered succession stages rivaling tropical rainforests in complexity." The discovery of methane-consuming archaea within older whale falls suggests these sites may influence deep-sea carbon cycles on a planetary scale.

What astonishes scientists most is the timescale of abundance. While most deep-sea habitats suffer chronic food scarcity, whale falls generate decades of plenty. Isotope analysis of mollusk shells growing on 80-year-old bones shows uninterrupted nutrition. Some polychaete worms appear to live their entire 30-year lifespans on a single skeleton. This challenges the paradigm that deep-sea organisms must be nomadic to survive. "We’ve found generations of the same clam species living and reproducing on ancestral bones," says deep-sea ecologist Craig Smith. "It’s like discovering an underwater city that renews its own infrastructure."

The phenomenon isn’t limited to whales. Megalodon teeth deposits and plesiosaur vertebrae fossils exhibit similar colonization patterns, hinting that this symbiosis predates human existence. Paleontological evidence from Miocene-era seafloors suggests bone gardens may have served as evolutionary crucibles, sheltering species through multiple mass extinctions. Modern threats like deep-sea mining and ocean acidification now endanger these fragile metropolises before we fully comprehend their ecological role. As submersible technology advances, each dive reveals new wonders—from bone-boring "zombie worms" (Osedax) to bioluminescent bacteria that paint skeletons in eerie blue halos.

Perhaps the most profound revelation lies in the gardens’ interconnectedness. Whale falls act as stepping stones across abyssal plains, allowing species to disperse between hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. Genetic studies show identical mussel populations spanning whale falls 500 miles apart, implying larvae hitchhike on deep currents. This raises provocative questions: Did whale falls enable life to colonize the entire ocean floor? Could their chemical signatures guide migratory species through the lightless void? Each answer uncovers deeper mysteries, reminding us that Earth’s greatest biodiversity may thrive where we least expect it—in the cathedral-like silence of the deep, where death begets life for centuries.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025