In the deep blue waters of the Pacific Northwest, a remarkable cultural phenomenon unfolds beneath the waves. For decades, marine biologists have observed an extraordinary pattern of vocal learning among the region's resident orca pods – a sophisticated form of dialect transmission that flows from grandmother whales to younger generations. This discovery has revolutionized our understanding of cetacean intelligence and social structures.

The matrilineal pods of killer whales, known scientifically as Orcinus orca, develop distinct vocal patterns that researchers liken to human regional accents. What makes this communication system truly exceptional is its method of preservation. While many animal species rely on instinctual calls, orcas demonstrate a learned vocal culture that requires careful instruction from elder females. Dr. Helena Marcheson of the University of Washington's Cetacean Research Program describes this as "the most complex non-human language curriculum we've ever documented."

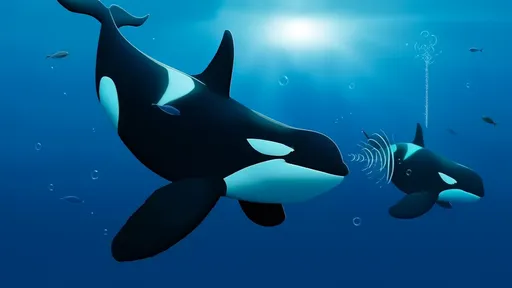

Grandmother orcas, often post-reproductive females who have survived into their 60s or 70s, assume the role of primary language instructors within their pods. These wise matriarchs spend hours each day leading what scientists now recognize as structured vocal lessons. Juvenile whales position themselves attentively beside their elders, mimicking sounds and receiving what appears to be corrective feedback when they err. The process bears striking similarities to human children learning their native tongue from grandparents.

Researchers have identified specific teaching techniques employed by elder orcas. The grandmothers frequently slow down their vocalizations when instructing calves, much like human caregivers using "baby talk." They also repeat certain call types more frequently during teaching sessions and appear to reward successful imitation with physical affection. Perhaps most astonishing is the observed progression in lesson difficulty – beginning with simple pulsed calls before advancing to the pod's more complex signature whistles.

The content of these language lessons extends far beyond basic communication. Through hydrophone arrays and underwater cameras, scientists have documented grandmother whales teaching regional hunting techniques that correspond with specific vocalizations. Different salmon runs, for instance, are associated with distinct call patterns that effectively serve as instructional labels. This linguistic mapping of hunting strategies allows knowledge to accumulate across generations, giving pods with strong grandmother figures a significant survival advantage.

Cultural erosion has become apparent in pods that have lost their elder females prematurely. Researchers tracking such groups note a concerning pattern: the simplification of vocal repertoires and disappearance of specialized hunting calls within two generations. This phenomenon mirrors what linguists observe in human communities when elder native speakers pass away without transmitting their knowledge. The parallel suggests that orca culture, like our own, relies heavily on intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Conservation efforts now emphasize protecting post-reproductive female orcas, recognizing their irreplaceable role as knowledge keepers. Marine protected areas are being designed with consideration for grandmother whales' teaching routes and schedules. Some researchers propose that the presence of elder females should become a key indicator of pod health when making population assessments. Their longevity appears directly tied to the cultural resilience of their family groups.

The implications of these findings extend beyond marine biology. Linguists and anthropologists have joined cetacean researchers to compare orca language transmission with human cultural preservation methods. The similarities challenge long-held assumptions about what constitutes "true" language and culture. As Dr. Marcheson notes, "We're witnessing a non-human society that maintains oral traditions, regional dialects, and pedagogical methods – concepts we once considered uniquely human."

Ongoing studies aim to decode the grammatical structures within orca vocalizations. Early analyses suggest that the sequencing of calls may follow rules comparable to syntax in human languages. Some researchers speculate that grandmother whales might teach narrative structures – ways of organizing information that allow pods to communicate complex concepts about their environment and history.

For the indigenous Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest, these scientific findings confirm ancestral knowledge about orca societies. Their oral traditions have long described killer whales as knowledgeable beings with complex family structures and communication systems. Modern researchers now work alongside indigenous knowledge keepers to better understand orca culture, creating a powerful fusion of traditional wisdom and contemporary science.

As climate change alters marine ecosystems and food sources, the role of grandmother whales becomes increasingly vital. Their accumulated knowledge may hold the key to pod survival in changing conditions. Researchers have observed elder females leading their pods to new feeding grounds during salmon shortages, using vocal patterns that suggest they're drawing on memories from their own grandmothers' teachings decades earlier. This intergenerational environmental knowledge could prove crucial for orca adaptation.

The study of orca language transmission continues to yield surprising discoveries. Recent observations indicate that some grandmother whales may teach "loan words" – vocalizations borrowed from neighboring pods during rare social interactions. This finding suggests a level of cultural exchange previously undocumented in cetaceans. Other researchers report instances of grandmothers apparently correcting multiple generations simultaneously, adapting their teaching methods to different age groups within the pod.

Marine parks and aquariums are reevaluating their approaches to captive orcas in light of these discoveries. The absence of grandmother figures and natural language transmission in captivity may explain observed behavioral differences between wild and captive orcas. Some facilities have begun introducing recorded wild orca vocalizations, though researchers emphasize that no artificial program can replicate the nuanced, responsive teaching of a live grandmother whale.

Public fascination with these findings has grown exponentially since the first studies were published. Wildlife tours in the San Juan Islands now highlight opportunities to observe grandmother whales teaching their pods. Responsible ecotourism operations use hydrophones to let visitors hear the language lessons in progress, with proceeds funding further research. This intersection of science and ecotourism creates new economic incentives for orca conservation.

The grandmother whales of the Pacific Northwest offer profound insights into the nature of language, culture, and intergenerational bonds. Their sophisticated teaching methods challenge us to reconsider intelligence in the animal kingdom and our relationship with other sentient beings. As research continues, each discovery underscores the importance of protecting these remarkable creatures and the complex cultures they sustain beneath the waves.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025