The hummingbird's metabolism operates at the edge of biological possibility, a feat of evolutionary engineering that allows these tiny creatures to sustain their high-energy lifestyles. Among their most astonishing capabilities is their ability to process nectar at speeds that defy conventional metabolic limits. This rapid energy conversion isn’t just impressive—it’s a matter of survival. To hover, dart, and evade predators, hummingbirds must extract and utilize energy from flower nectar almost instantaneously. Scientists have long been fascinated by how their bodies achieve this, and recent research is beginning to unravel the secrets behind this extraordinary physiological adaptation.

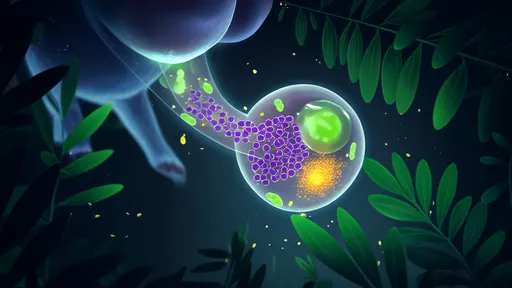

At the heart of this phenomenon lies the hummingbird’s unparalleled sugar metabolism. Unlike most animals, which process sugars through gradual oxidative pathways, hummingbirds have evolved a system that bypasses many of the usual metabolic bottlenecks. Their muscles, particularly the pectoral muscles responsible for flight, contain an exceptionally high density of mitochondria—the cellular powerhouses that generate ATP. But sheer mitochondrial abundance isn’t the only factor. These mitochondria are uniquely optimized to process sucrose and fructose at breakneck speeds, converting nectar into usable energy in a matter of seconds rather than minutes.

The role of enzyme efficiency cannot be overstated. Hummingbirds produce specialized digestive enzymes, including sucrase and hexokinase, at levels far exceeding those found in other birds. These enzymes break down complex sugars into glucose and fructose almost immediately upon ingestion. What’s more, their intestinal transporters are hyper-efficient, shuttling these simple sugars into the bloodstream with minimal delay. This rapid absorption means that within moments of consuming nectar, a hummingbird’s muscles are already receiving the fuel needed to sustain their frenetic wingbeats, which can exceed 50 strokes per second.

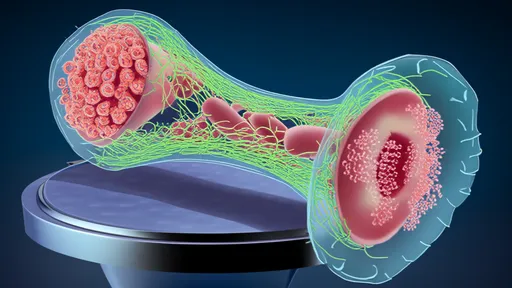

But speed isn’t the only challenge—hummingbirds must also avoid the pitfalls of excessive sugar intake. Most animals, including humans, would suffer severe consequences from the sheer volume of sugar that hummingbirds consume daily (sometimes exceeding their own body weight in nectar). Yet hummingbirds exhibit no signs of diabetes or metabolic distress. Researchers believe this resilience stems from their ability to tightly regulate blood glucose levels, ensuring that the sugars they ingest are either immediately burned for energy or stored as glycogen with remarkable efficiency. Their kidneys also play a crucial role, rapidly filtering out excess sugars before they can cause osmotic imbalances.

Another fascinating aspect of their metabolism is how it adapts to fluctuating energy demands. During flight, a hummingbird’s metabolic rate can skyrocket to more than 10 times that of an elite human athlete in peak exertion. Yet when at rest, particularly during torpor—a hibernation-like state they enter at night—their metabolism slows to a near standstill. This metabolic flexibility is governed by intricate hormonal controls, including rapid shifts in insulin sensitivity that allow them to switch between energy storage and expenditure modes seamlessly.

Recent studies have even uncovered surprising parallels between hummingbird metabolism and certain human metabolic disorders. For instance, the genes responsible for their rapid glucose uptake share similarities with mutations found in rare cases of human hypermetabolism. Understanding these mechanisms could hold implications for diabetes research, offering insights into how extreme sugar processing might be managed or even harnessed. Some scientists speculate that elements of hummingbird physiology could one day inform treatments for metabolic syndrome or energy deficiencies in critically ill patients.

Yet for all we’ve learned, mysteries remain. How exactly do hummingbirds avoid oxidative damage from such high metabolic activity? Their cells must contend with an onslaught of free radicals generated by their relentless energy production, yet they show little signs of the cellular wear and tear that would plague other organisms. Some researchers point to exceptional antioxidant defenses, while others theorize that their cells have evolved superior repair mechanisms. Unlocking these secrets could revolutionize our understanding of aging and metabolic resilience across species.

In the grand tapestry of evolution, hummingbirds stand as a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Their ability to instantaneously convert flower nectar into flight represents one of the most extreme examples of metabolic adaptation in the animal kingdom. As research continues to peel back the layers of this biological marvel, each discovery not only deepens our appreciation for these tiny aerial dynamos but also sheds light on the fundamental principles of energy, life, and the astonishing plasticity of living systems.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025