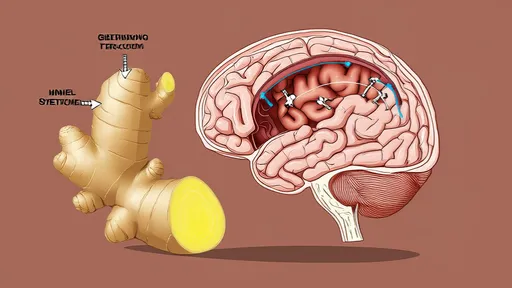

For centuries, traditional healers and grandmothers alike have sworn by ginger's ability to soothe an upset stomach and quell the rising tide of nausea. From morning sickness to seasickness, the gnarly root has been a go-to remedy, its efficacy passed down through generations as folk wisdom. While its benefits were widely acknowledged, the precise biological mechanisms behind ginger's anti-emetic power remained shrouded in mystery, a secret locked within its pungent, aromatic compounds. Modern science, with its sophisticated tools and relentless curiosity, has finally begun to pick that lock, revealing a fascinating and surprisingly direct action on the very systems that control nausea and vomiting in the human body.

The journey to understanding ginger begins with understanding vomiting itself. Vomiting is not a simple act; it is a complex, coordinated reflex orchestrated by the brain. The primary command center for this unpleasant process is a region known as the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the area postrema of the brainstem. This unique region lacks a full blood-brain barrier, allowing it to constantly sample the blood and cerebrospinal fluid for toxic substances. When it detects something amiss—be it a toxin, a medication like chemotherapy drugs, or the hormonal shifts of pregnancy—it sends an alarm signal to another brain region called the vomiting center, which then coordinates the muscular contractions necessary for emesis.

For decades, the prevailing theory was that ginger worked primarily in the digestive tract, calming stomach spasms or speeding up gastric emptying. However, recent pharmacological investigations have unveiled a much more sophisticated and central mode of action. The key players are ginger's bioactive compounds, primarily gingerols and shogaols. These substances are what give ginger its characteristic bite and aroma, and they are now understood to be potent natural medicines. Researchers have discovered that these compounds exert a significant influence on the serotonin system, specifically by interacting with 5-HT3 receptors.

Serotonin, or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a critical neurotransmitter involved in initiating the vomiting reflex. In the gut, large amounts of serotonin are released by enterochromaffin cells in response to irritants or toxins. This serotonin then binds to 5-HT3 receptors on vagal nerve fibers, which carry the "nausea signal" directly to the brain's vomiting center. Simultaneously, in the brain itself, 5-HT3 receptors in the CTZ are also activated by various emetic triggers. Conventional anti-nausea drugs, such as ondansetron, work by blocking these 5-HT3 receptors, effectively shutting down the signal. The groundbreaking revelation is that gingerols and shogaols act as natural 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. They bind to these receptors, preventing serotonin from docking and initiating the cascade that leads to vomiting. This places ginger in the same pharmacological league as some of the most effective modern anti-emetic medications, albeit in a natural, complex form.

But the mechanism does not stop there. Ginger's prowess appears to be multi-targeted, a hallmark of many effective natural remedies. Beyond serotonin antagonism, evidence suggests that ginger's active components also interact with the cholinergic pathway and neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors. The cholinergic system, involving the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, is another pathway implicated in gastric motility and the vomiting reflex. By modulating this system, ginger may help normalize stomach rhythms that are disrupted during nausea. Furthermore, the NK1 receptor pathway, which is the target for a newer class of anti-emetic drugs like aprepitant, is also influenced by ginger compounds. This multi-pronged attack allows ginger to effectively counter nausea triggered by a wide array of causes, from motion and pregnancy to anesthesia and chemotherapy.

The implications of this mechanistic discovery are profound, particularly for patient care. For pregnant women suffering from morning sickness, ginger offers a compelling, non-pharmacological alternative to drugs, which are often approached with caution during pregnancy. Its natural origin and long history of safe use make it an attractive option. In oncology, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains a debilitating side effect for many patients. While powerful pharmaceuticals exist, they are not always effective for everyone and can come with their own side effects. Ginger, used as a complementary therapy, has shown significant promise in clinical trials to reduce the severity and frequency of CINV, potentially improving patients' quality of life and their ability to adhere to treatment regimens.

This scientific validation also bridges a long-standing gap between traditional medicine and modern clinical practice. For generations, the use of ginger was based on anecdotal evidence and empirical knowledge. It worked, but no one knew precisely how. Now, with a clear biochemical pathway identified, physicians and researchers can approach ginger with a new level of confidence and precision. It transforms the remedy from an "old wives' tale" into an evidence-based therapeutic agent. This demystification does not diminish ginger's value; rather, it enhances it, providing a solid scientific foundation for its continued and expanded use.

Looking ahead, the revelation of ginger's mechanism opens up new avenues for research and application. Scientists are now better equipped to study potential synergies between ginger extracts and conventional anti-emetic drugs. There is also growing interest in standardizing ginger supplements to ensure consistent levels of the active gingerols and shogaols, moving beyond the variability of raw root or simple teas. Furthermore, understanding this mechanism provides a template for investigating other traditional remedies. If ginger works by blocking key nausea receptors, what other natural compounds might hold similar, yet undiscovered, potential?

In conclusion, the humble ginger root has been elevated from a kitchen spice and folk remedy to a subject of serious pharmacological inquiry. The discovery that its primary active compounds, gingerols and shogaols, function as natural antagonists to the 5-HT3 receptor—a key trigger for vomiting—has finally provided the scientific explanation for its centuries-old reputation. This mechanism, complemented by actions on other neural pathways, reveals a sophisticated, multi-targeted approach to quelling nausea. As research continues to unfold, this ancient root is poised to play an increasingly validated and vital role in modern therapeutic strategies, offering effective, natural relief for one of humanity's most common and distressing ailments.

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025

By /Oct 31, 2025